| |

|

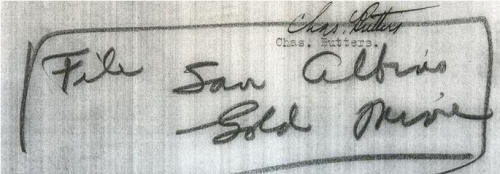

Charles

Butters on Sandino's return to San Albino Mine

in June 1927

In mid-1926 Sandino returned from exile

in Mexico and journeyed from the city

of León

up to the San

Albino Mine in the northeastern Segovias, owned

by US citizen Charles Butters, where he got a

job as a pay clerk. In retrospect, his

decision to seek employment among politically

oppressed and economically exploited wage

workers in a mining enclave dominated by US capital could not have been

more shrewd.

In mid-1926 Sandino returned from exile

in Mexico and journeyed from the city

of León

up to the San

Albino Mine in the northeastern Segovias, owned

by US citizen Charles Butters, where he got a

job as a pay clerk. In retrospect, his

decision to seek employment among politically

oppressed and economically exploited wage

workers in a mining enclave dominated by US capital could not have been

more shrewd.

As the civil war

between Liberals and Conservatives heated up in

the summer and fall of 1926, Sandino organized

the nucleus of what later became his Defending

Army — which appears to have been his plan all

along. In late October 1926, Sandino and

the mine workers rose up in rebellion against

the Conservative regime dominated by Emiliano

Chamorro and Adolfo Díaz and their local

Segovian cronies. In early

November, Sandino's Liberal rebels attacked the

Conservative garrison at El Jícaro. Over the

next seven months, as civil war ravaged the

country, Sandino emerged as one of the top

Liberal generals, at one point commanding

upwards of 1,000 troops.

After 4 May

1927, the day that Liberal Commanding General

José María Moncada (at the behest of ousted

Liberal President Juan Bautista Sacasa) signed

the Espino Negro Accord (or Treaty of Tipitapa),

Sandino became the only Liberal general to

refuse to disarm. Instead he and a handful of

followers headed back up to San Albino Mine to

begin their rebellion against the vendepatria (country-seller) Moncada and the US

Marine intervention.

Thus Sandino's

rebellion against the US government's

"trampling underfoot" of Nicaraguan national

sovereignty began in the

same US-owned mining enclave where his uprising

against the Conservative Díaz

& Chamorro regime began eight months earlier.

Only now, the civil war between Liberals &

Conservatives was formally over, and the fight

against the Marines and Guardia Nacional was

about to begin.

Charles Butters' narrative offers a

remarkable description of Sandino's return to

San Albino and portrait of his organizing

efforts among the mine workers. One factual error concerns the

date of Sandino's return to the region — in fact it was probably closer to June 19, as

seen in the next page. Read "against the

grain" of its

condescending and denunciatory tone, Butters' account

offers not only a concrete narrative of events

but valuable insights into the discourse used by

Sandino to mobilize followers, the nature of his

nationalist message and vision, and how that

message and vision resonated among Segovianos.

(Left: Sketch of Charles Butters kind

courtesy of Dan Plazak, engineer and intrepid

mine explorer, from his website

here)

Charles Butters' narrative offers a

remarkable description of Sandino's return to

San Albino and portrait of his organizing

efforts among the mine workers. One factual error concerns the

date of Sandino's return to the region — in fact it was probably closer to June 19, as

seen in the next page. Read "against the

grain" of its

condescending and denunciatory tone, Butters' account

offers not only a concrete narrative of events

but valuable insights into the discourse used by

Sandino to mobilize followers, the nature of his

nationalist message and vision, and how that

message and vision resonated among Segovianos.

(Left: Sketch of Charles Butters kind

courtesy of Dan Plazak, engineer and intrepid

mine explorer, from his website

here)

|

|

|

San Albino Gold Mines.

June 21, 1927.

General Sandino, a young man of about 30,

appeared at my office at San Albino about a year

ago, seeking a position in a clerical capacity,

stating that he had just come down from

Guatemala where he had been employed in the

office of a mining company. I gave him

employment as a file clerk in the store at $25

per month. He was neither brilliant nor apt at

the work. He spoke considerable English.

During an interval of probably three months, he

busied himself by recruiting miners and other

employees of the company into a skeleton force

of revolutionaries. All this was unbeknown to

me, till one fine morning he disappeared with a

small group of my men and took to the woods,

where he was rapidly joined by others of the

Liberal party, and in some manner he was shortly

afterwards supplied with sufficient arms to

enable him to attack the government troops at

Jicaro, where both sides claimed the victory.

Shortly thereafter the government troops were

gradually withdrawn from [the] Jicaro district,

since which time they have never returned and he

became known as the Sacasa representative in

Segovia. Some months later, he claimed to have

made a trip to Puerto Cabezas and brought up

supplies of arms and ammunition, via the Coco

River, which were freely distributed through the

district, after which the whole district was

completely under his dominion and later under

Moncada's orders he marched to Jinotega. He

remained in the active service of Moncada for

some months.

Not being willing to lay down his arms, he

returned to the district, well supplied with

money, the best of arms and ammunition, well

dressed and well mounted, and declared himself

enemy of the Americans and of Moncada as well.

On arrival at San Albino, about the end of May,

he appeared with a troop of about 50 men,

stating that he had come for powder and to kill

Americans. He demanded from me, upon pain of

death, the delivery to him of 500 lbs. of

dynamite, 1500 caps and 200 feet of fuse, with

the repeatedly expressed object of killing

Americans. I was obliged to furnish these

articles. He thoroughly frightened our entire

white staff.

This statement of killing the Americans was in

line with all his private statements, which I

later ascertained he had made continually while

in my employ. That all the Americans should be

killed or driven out of the country. This

statement seemed to have emanated from Mexico,

where he claims he was an officer in

revolutionary force for 11 years, and constantly

preached the doctrine of Boshevikism always

carrying with him the black and red flag with

skull and cross bones which he declares to be

the emblem of bolshevekism.

He is a socialist and a fanatic. He [is]

constantly preaching the brotherhood of man and

claiming that there are no officers in his army,

but all comrades, and continually repeating and

emphasizing the friendship that they should have

for Mexico, because of the contribution of arms

and ammunitions which he claims was a free gift

of that country to enable them to fight off the

Americans influence always patting their rifles

as he handed it to the man who volunteered, as a

gift from Mexico to the Nicaraguan soldiers to

enable him to gain his freedom from

imperialistic Americans. "Mexico our friend,

America our enemy, always."

When calmly talked to, he would state that he

didn't intend to kill unoffending Americans but

only American soldiers, but this is a

distinction which his men cannot be expected to

draw. He has with him Mexican officers. One of

his bugler was rather well educated. He states I

came from Mexico to prepare this district to

take part in the revolution. As soon as my

mission is over, I shall return. Of course he

had full knowledge of the impending revolution

aided by Mexico and has taken an active part.

/s/ Charles Butters.

NA127/198/GN-2 File 1928

|

Below: Aerial view of San

Albino Mine looking north, late 1927.

US

National Archives, Record Group 127, Entry

38, Box 29.

SanAlbinoMine-Air2.jpg)

|

Ancillary Documents and Photographs

on San Albino Mine

The following

documents can be accessed as JPEG files:

|

1.

Charles

Butters, San Francisco CA to General Augustino

Sandino [sic] via Pedro Jose Zepeda, Mexico

City, 21 June 1930, USNA127/38/30.

|

|

(p. 2)

|

|

2.

Charles

Butters, Berkeley CA to Gen. Calvin B. Matthews,

Managua, 16 Nov. 1931.

|

|

(p. 2).

|

|

3.

Charles

Butters to Gen. Calvin B. Matthews, 18 Nov.

1931.

|

|

4.

Present

Condition of Mine Property at San Albino, GN

District Commander John Hamas to Jefe Director

GN, 22 Dec. 1931.

|

|

(p. 2).

|

|

5.

Charles

Butters to Gen. C. B. Matthews, 16 Feb. 1932.

|

The following

photographs of the ruins of San Albino Mine,

taken in early 2007, were kindly provided by

Mr. Dan Plazak, a geologist, engineer, and author of a

fascinating history of mining scandals in the US

mining industry,

A Hole in the Ground with a

Liar at the Top, University of Utah Press,

2006. His account of finding the San

Albino Mine can be found

in an MSWord file

here. Thanks Dan!

|

|

top of page

|

|

|